Edmonton Design Committee (EDC): A Guide to the Review Process

Situate is an urban planning consulting firm specializing in rezoning, permit and subdivision coordination services for awesome infill projects. In our How To articles we dissect the ins and outs of navigating permits and approvals.

If you’ve glanced at the news lately, you’ve probably noticed that infill is having a moment. It’s front and centre in headlines, community conversations, and planning policy discussions not just in Edmonton, but across many cities. But what exactly is infill? Why is it attracting so much attention? Is it really all downside and no upside?

In this blog, we’ll unpack why infill—or building new housing within existing communities— matters for the future of growing cities.

At its core, infill means developing or redeveloping vacant or underused land within established communities. It can take many forms—residential, commercial, industrial, institutional, or mixed-use.

We know people are most familiar with, and most curious about, redevelopment in residential areas. It also happens to be where Situate specializes— navigating rezoning and permit processes for housing projects—so that’s what we’ll focus on in this blog.

In many cases, residential redevelopment means replacing (though not always) older, vacant, or unwanted buildings with new homes. These projects commonly look like a small backyard suite, a single detached house, a row of townhomes, or even a low-rise apartment building.

In Alberta, Municipal Development Plans guide urban development and redevelopment. For example, Edmonton’s City Plan is the big-picture playbook for the city’s future growth. It outlines where new housing should go, and why it matters. Edmonton’s City Plan sets an ambitious target: 50% of all new housing units and 600,000 new residents will be welcomed into established neighbourhoods (mostly within Anthony Henday Drive) as the city continues to grow.

In Edmonton, the City Plan doesn’t stand alone—it comes with a set of District Plans. Think of them as the zoomed in version of the big picture. The city is divided into 15 districts, each with its own strategy for how growth should play out. District Plans take the city-wide goals and translate them into neighbourhood-level direction—guiding rezoning decisions and pinpointing where different kinds of housing fit best. (Want to know more about City Plan and District Plans? We have a full blog post on the topic).

And finally, at the most detailed level, the Zoning Bylaw sets the rules for each site—what can be built today, how tall or large it can be, and how land can be used.

Different municipalities may have different planning documents, but the general approach is similar: big-picture vision, area-level guidance, and site-specific rules. (The good news? Situate makes sense of all these layers, saving you from the thrilling pastime of deciphering bylaws on a Friday night).

Now that you know what redevelopment is, the next question is: why do (some) cities want more of it? Simply put, it comes with a lot of upsides. Redevelopment is better for the environment, makes better use of your property tax dollars, and helps ease housing pressures by adding more housing and more housing options.

Residential redevelopment shapes four key parts of city life: the homes we live in, the businesses we enjoy, the ways we get around, and how we share the costs.

Over time, household sizes and structures have changed, but our housing options haven’t quite kept up. These days families are smaller and lifestyles are more varied than ever. Yet in many neighbourhoods, the choices for homes are still limited—single detached houses on one side, high-rise towers on the other, with very little in between.

Enter middle housing. Think of it as the “in-between” housing option: It’s the duplex on the corner, the row of townhomes down the street, or the low-rise apartment above your favourite coffee shop. A lot of infill redevelopment is middle housing.

Why does it matter? Because not everyone wants—or needs—a four-bedroom house or a tiny apartment unit. Families, seniors, students, and professionals all benefit from having housing choices that fit their lives. Middle housing also helps neighbourhoods transition more smoothly between low- and high-density areas, and it adds new homes right where amenities, parks, and schools already exist.

Empty tables and “for lease” signs aren’t good for anyone—but more neighbours can change that. When enough people live nearby, the corner café keeps brewing, the neighbourhood pub keeps pouring, and the local shops have steady customers. Suddenly, errands and evenings out don’t have to come with a traffic jam or a hunt for parking.

Here’s something you might not know: one in five Edmontonians don’t drive to work according to the 2021 federal Census. This might be your coworkers who don’t drive, neighbours who rely on transit, and people who simply choose another way to get around. For the rest of us, driving is an added expense and time in traffic is precious time we don’t get back. Add to the fact that studies show walkable neighbourhoods can actually make us healthier and happier. Yet so many parts of our city aren’t built for walking.

That’s where redevelopment makes a difference. When more people live closer together, transit has the ridership it needs to run more often and more reliably. Sidewalks and bike routes benefit too, since higher use creates stronger demand for upkeep. And the result? Neighbourhoods where walking, cycling, or hopping on the bus is often the simplest (and most enjoyable) way to get around.

Cities don’t have endless revenue streams—they rely almost entirely on property taxes. Building brand-new neighbourhoods at the edge of the city means building brand-new roads, sewer pipes, fire halls, libraries, and parks to maintain. It’s expensive, and the tax base doesn’t always stretch far enough to keep up. The numbers prove it: three new suburban neighbourhoods in Edmonton were projected to cost $1.4 billion more than they would generate in taxes, grants, and other revenues.

Redevelopment flips that equation. A new row of townhomes or an apartment building on a vacant lot—or replacing an aging or abandoned house—can generate more tax revenue than what was there before, all without adding the massive servicing costs that come with expansion. Existing roads, utilities, parks, and transit lines get used more efficiently, stretching tax dollars further and saving everyone money. For residents, the payoff shows up in everyday life. Shorter and fewer car trips mean less money spent on gas, insurance, and maintenance. With more neighbours around, the costs of maintaining and upgrading utilities are shared more broadly, directly saving everyone money. And as new people move in, neighbourhoods stay lively—schools stay open, parks get more use, and local services grow to match the demand.

There are some persistent questions about urban redevelopment that come up time and time again, so let’s talk about them!

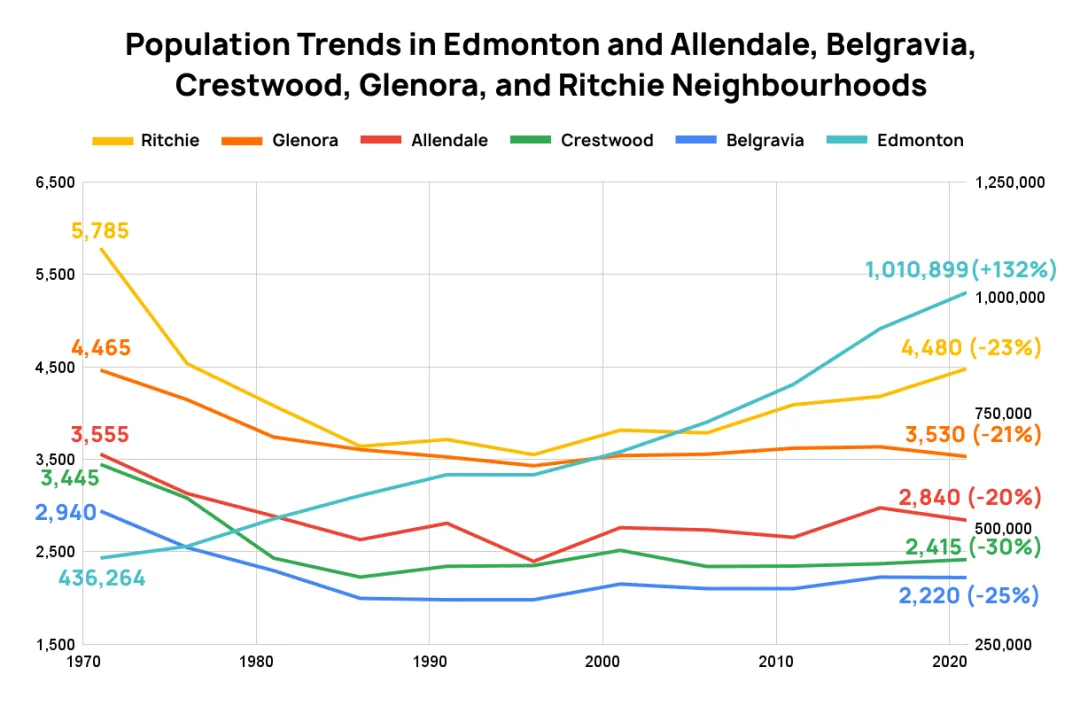

The truth is, many mature neighbourhoods actually have fewer residents today than they did decades ago. Over time, children moved away or people moved to the suburbs, leaving central areas well below the capacity they were originally designed for.

Household sizes have also changed. Post-war homes once held large families—several kids, and sometimes even grandparents under the same roof. Today, families tend to be smaller, which means fewer people living in the same houses on top of the broader population decline in mature neighbourhoods.

The result is a striking contrast: according to federal census data, while Edmonton’s overall population has steadily climbed, many mature neighbourhoods have seen drops of more than 20% from their peak. The graph below illustrates this change clearly.

Central neighbourhoods are attractive because they’re well connected. Good transit, nearby shops and services, ride-sharing apps, and carshare options like Communauto all reduce the need for a household to own multiple vehicles.

The numbers tell the story. According to the 2021 Census, 78.4% of Edmontonians commuted by car—but in core areas like Downtown and Garneau, that figure drops sharply. Just over half of residents in those two neighbourhoods didn’t drive to work, and similar trends appear in other mature neighbourhoods such as McKernan, Old Strathcona, and Belgravia, where fewer people rely on cars for their commute. Cycling is also on the rise: Eco-Counter data from downtown and the university area shows ridership between April and August jumped from 573,400 in 2023 to 654,705 in 2025—an impressive 14.2% increase (and yes, people also biked during the winter months too).

Speaking of parking, on average, based on 2024 permit data, the City Administration found that developments in mature neighbourhoods provide 0.48 stalls per dwelling unit—roughly one stall for every two homes. They also noted that a four-unit row house with four secondary suites is typically built with a four-car garage, meaning many new projects are still providing on-site parking. On top of that, the City’s comprehensive parking study found that, overall, parking is oversupplied across geographies and land uses, even if some specific neighbourhoods see higher occupancy rates at certain times of day.

Put simply: more neighbours doesn’t always equal neighbourhood gridlock. With strong transit, rising cycling rates, walkable amenities, and smarter parking supply, mature neighbourhoods can welcome new residents without overwhelming the streets.

In many established neighbourhoods, much of the infrastructure is actually underused. Roads, sewers, and schools were originally built to serve larger populations than they do today.

Modern technology also helps. Today’s dishwashers, washing machines, and toilets use far less water and energy than older models, which leaves extra capacity in the system.

And when new housing is proposed, it doesn’t get a free pass. Every project goes through EPCOR’s review, and if upgrades to water or sewer lines are needed, the developer is responsible for completing them before construction can move forward.

There’s no clear evidence that new housing directly causes property values to rise or fall. City assessors base their evaluations on factors like home style, size, age, condition, special features, and location—not simply whether redevelopment is happening nearby.

What new housing does bring is more neighbours, and with them, more spending power. That added demand supports local shops, services, and amenities, which helps keep neighbourhoods vibrant and appealing.

New development has to meet landscaping standards in the Zoning Bylaw—including requirements to plant or preserve trees and shrubs. Public trees, like those on boulevards and right-of-way, are protected and can’t be removed for redevelopment. Sometimes existing trees on private properties do need to come down—for example, to make way for foundations and utilities. But again, new development always has to include a certain number of trees and shrubs, so greenery gets added back in.

On top of that, new homes are built to modern energy-efficiency standards, which lowers their long-term environmental footprint. And at the bigger scale, each project built within established neighbourhoods helps reduce pressure to extend development into farmland, wetlands, and other environmentally sensitive areas on the city’s edge.

Adding more homes in existing neighbourhoods isn’t only about putting up new buildings—it’s about keeping communities lively and making sure they grow in ways that work for the people who live there as well as new residents moving in. It means using the roads, schools, and parks we already have more efficiently, giving people more housing options, and adding energy to the places we already call home.

At Situate, we help make this happen by handling the rezoning and permit process from start to finish—so our clients can stay focused on their ideas while we take care of the approvals. Because in the end, it’s not just about buildings; it’s about supporting stronger, more welcoming communities.

This article was written by Situate, Edmonton’s planning consulting firm specializing in strategy and approvals for awesome infill and urban (re)development projects.

Our cities need more housing, and we don’t think anything should stand in the way. Book a call and let’s map the fastest path to yes.